The evolution of money in America expresses the nation’s values and intellectits contradictions. In this not-so-lustrous yet vividly rendered history of American currency, certain truths come to the fore: that our currency, like the country, is progressively improvisational and a bit haphazard, which is a funny thing to say for a system that so desperately seeks the appearance of solidity. That it somehow retains the semblance of “legal tender” while simultaneously being something else entirely, in this case a Treasury Department marketing riff, meant to convince us all of the awe-inspiring power and security of our pocket change, not to mention our artistic talent and divine blessings.

How American Bills Came to Be America’s First Paper Money

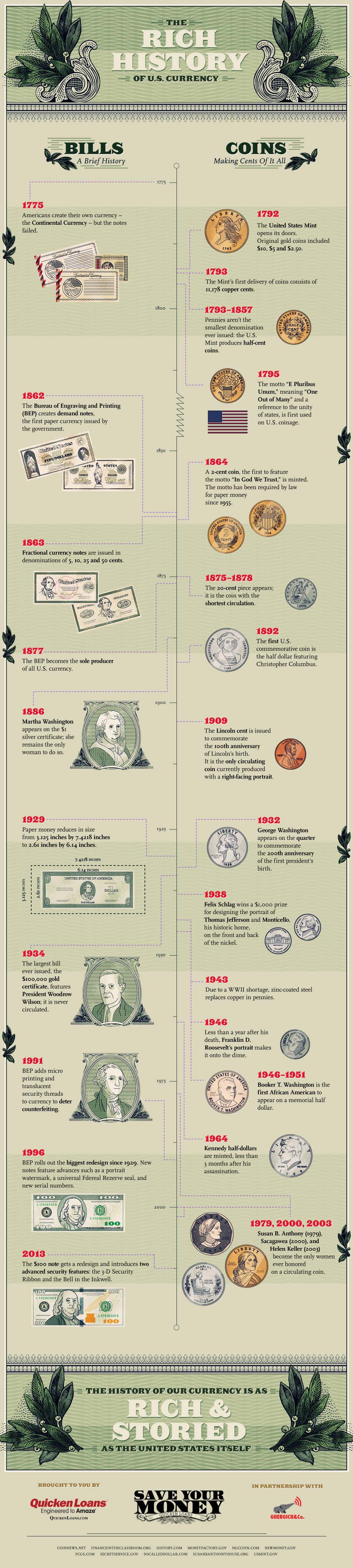

The fledgling republic found itself in urgent need of a real currency less than a year after declaring independence. What we first had was something called Continental Currency, but that proved very weak as a medium of exchange not just because it had to fight for a reputation of being a reliable currency, even among potential users. But also because the Congress that created it was at war with the British Empire and was trying to fund that war. We don’t remember Continental Currency very fondly today, it’s kind of our first lesson in how to make bad paper.

Since 1862, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing has performed the vital and secure function of creating and controlling the look of U.S. paper money. By 1877, it had become the unquestioned master of the production of American paper currency. While the Founding Fathers deserve credit for attempting to create a national currency. The failure of the Continental notes ensured that a funny old story would keep being told: overconfident monetary schemes with insufficient backing. If we’re going to put Santa Fe and its creators on our currency then at least it’s not an occasion for putting ghost stories on our banknotes.

A Concise Summary of U.S. Coin History

U.S. coins from the beginning offered and kept a tantalizing variety of designs from the nearly worthless half-scent to the amazing $10 gold piece. But real coinage action didn’t start until 1795, and even then, the mint held to what was perceived as safe, sound, and not very exciting design, all while some high-profile, low-profile artists were lurking around. (One great ongoing design mystery is why the United States holds to so few actual coin models, with so few real changes, and how many of its model changes are just disguised model changes or redesigned backdrops.) Still, U.S. coins serve up an ongoing appearance of variety, even as their overall appearance inspires the same long-ago “what’s next?” since the stuff that underpins coin designing is also part of art history.

Usability and Counterfeiting: Is There a Correlation?

The last fundamental redesign of United States currency was in 2013, and while it undoubtedly incorporated new features to foil counterfeiters, many of its changes seemed intended to make our cash a little more user-friendly. But counterfeiting cash has gotten a lot harder, and using cash has gotten a lot easier, so we should probably just accept that this is the way things are and carry on.

Much like the dollar, the 1929 bill’s value has diminished. Can even the most impressive, counterfeit-proof measures put into place today help restore our lost faith in paper money? The impersonal, almost naked, quality of our cash underscores the larger question hanging over it: If we’re to have paper money, shouldn’t it at least function as a public artwork with some nearly universal appeal that, through reference or even allegory, speaks to our time and to what we value? Our current cash seems not to function as a public artwork at all. In haphazard fashion, we appear to choose figures for it that, in some instances, serve our past’s idea of historical merit without really reaching for anything that could function as a present-day “hero” or community vision worthy of artistic representation.

Currently, only two of the 15 individuals represented on U.S. coins and bills are women: Sacajawea and Susan B. Anthony. And shifts are something we know about in this country. It’s not that newer is necessarily better; unlike Continental notes, today’s dollar bill has technology working for it. But it’s not just about the dollars and cents: the dollar’s history which is 240 years and counting tells us something even more powerful. With every new bill, the better to curvilinear surfacize it, we often for shifty reasons tell ourselves something about how we want to see ourselves or how we see the nation in the time being. If currency is America’s universal performative, then its history is a kind of national pathology that we ought to understand and to understand better to face these things we don’t always talk about.